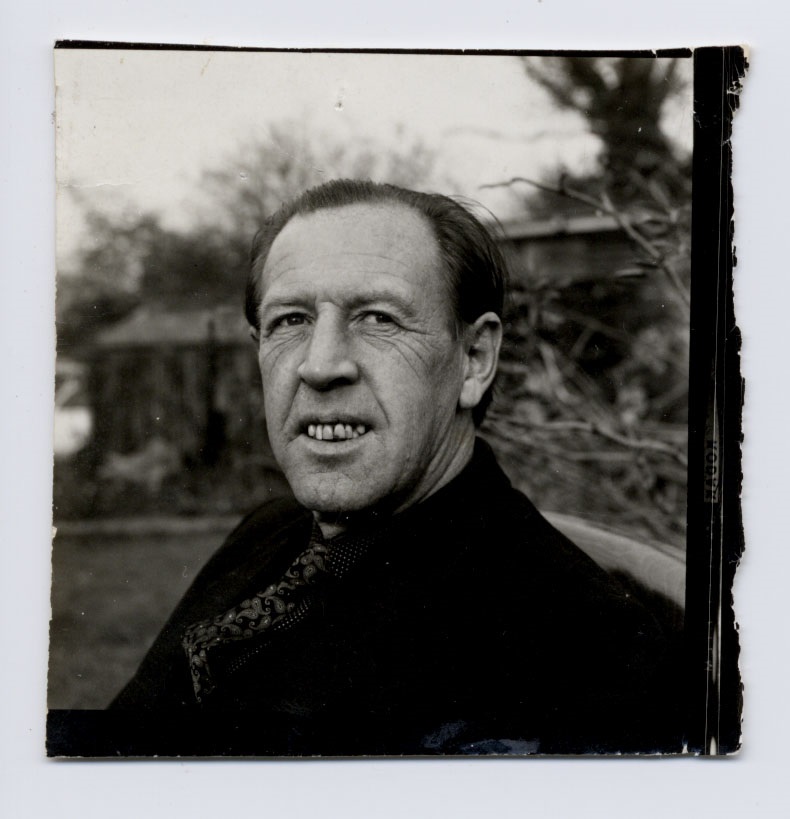

Raymond Williams

Raymond Williams was born on 31 August 1921 in Pandy, near Abergavenny, Monmouthshire, the only child of Henry Joseph Williams, a railway signalman, and his wife Esther Gwendoline (née Bird). Aspects of his upbringing and the lives of his parents are conveyed in his first novel, Border Country (1960), most centrally the ways in which the General Strike and Lockout of 1926 exposed strains within a rural community and continued to inform the possibilities and limitations of class politics and action into the postwar era. The central character is known as Will by his parents, though he is Matthew on his birth certificate and that is the name that he uses in his working life as an academic in England. This reflects Raymond Williams’s own experience of being known as Jim in the border country.

Educated at King Henry VIII Grammar School in Abergavenny, Jim/Raymond, like Will/Matthew in Border Country, went on a state scholarship to study English at Cambridge in 1939. His period at Trinity College was interrupted by call up in 1941. He was commissioned in 1942 and fought with the No. 21 anti-tank regiment in the Normandy campaign and on through Belgium and the Netherlands to Germany. He attained the rank of captain, and these experiences inform the war scenes in his fifth novel, Loyalties (1985). The fact that he fought against fascism contributed to his later authority as an intellectual of the post-war New Left and distinguished his generation (which included E. P Thompson, Richard Hoggart and Gwyn A. Williams) from the later ‘new’ New Left of the 1960s (Perry Anderson, Tom Nairn, Terry Eagleton) who criticised the earlier generation for its ‘humanism’ and reliance on untheorised lived ‘experience’ as a basis for analysis.

The war years also saw his marriage to Joyce (Joy) Mary Dalling (d. 1991) from Barnstable whom he met at Cambridge when the London School of Economics was evacuated there. They had two sons, Ederyn and Madawc, and one daughter, Merryn. Joy directed her intelligence in support of her husband’s work, and the central role that she played in the development of his ideas and the research for his novels (especially the two volumes posthumously published as People of the Black Mountains I and II (1989, 1990)) is yet to be fully documented.

Having gained a first-class honours degree in 1946, Williams became staff tutor of the Oxford University Extra-Mural Delegacy (1946-1961), based in east Sussex. Informed by Cambridge critic F. R Leavis’s belief in the ways in which the close reading of literature could enhance individual lives and transform social values, Williams’s first editorial initiatives and publications were on the ways in which literary texts embody – in their form and content – the often conflicting ‘structures of feeling’ that inform society and politics. He was editor of The Critic and Politics and Letters (which absorbed the former), played a bridging role as the Universities and Left Review combined with the New Reasoner to create the influential New Left Review, and published Reading and Criticism (1950), Drama from Ibsen to Eliot (1952), Preface to Film (with Michael Orrom) (1954), and Drama in Performance (1954). The essays of this period (collected by John McIlroy and Sallie Westwood as Border Country: Raymond Williams in Adult Education (1993)) testify to the extent to which he drew on his work as extra-mural educator in the creation of his career-making volume Culture and Society (1958). A dissection of the meaning of ‘culture’ in English thought since industrialisation, the volume is widely identified as a progenitor for contemporary cultural studies. The often-generous engagement with pre-socialist and even anti-socialist thinkers (from Edmund Burke to T. S. Eliot) proved disconcerting to readers on the Left, but allowed Williams, characteristically, to access neglected sources of social critique and to forge a socialist cultural criticism that would prove resistant to the whims and fashions of the political and cultural climate. The more overtly political and socially engaged The Long Revolution (1961) followed, a volume that foregrounded the ways in which narrow political and economic perspectives left out vital areas of social experience, and explored the ways in which developments in education and communications had opened up democratic possibilities in the past, and offered new avenues for human agency in the present.

In the introduction to The Long Revolution, Williams noted that ‘this book and Culture and Society, and my novel Border Country’ complete ‘a body of work which I set myself to do ten years ago’. 1961 did indeed seem the culmination of one period and the beginning of another. Williams returned to Cambridge that year as lecturer in English and fellow of Jesus College, where he remained until his retirement in 1983, becoming the university’s first professor of drama in 1974. Though not primarily remembered as a critic of drama, his Modern Tragedy (1964), essays in Writing in Society (1983) (including his inaugural lecture of 1974, ‘Drama in a Dramatized Society’) and regular reviews of television and film in The Listener (1968 – 1974) testify to the centrality of dramatic forms in his thought. Williams described himself a writer, believing his novels to be of equal importance to his critical studies (a view not widely shared by later commentators). In addition to Border Country, Loyalties and People of the Black Mountains mentioned above, Second Generation (1964) and The Fight for Manod (1979) completed the ‘Welsh Trilogy’ while The Volunteers (1978) was a stand-alone thriller centered on a once-radical journalist exploring the murder of a worker during a period of militancy in the south Wales coalfield.

The 1960s saw a shift in political allegiances. Having been a Communist on going to Cambridge, Williams was unaffiliated in the post-war years, though broadly shared his father’s allegiance to the Labour party and campaigned for Harold Wilson in 1964. The May Day Manifesto – developed in collaboration with historian E. P Thompson and critic Stuart Hall, distributed for discussion and commentary by socialist groups in 1967 with a fully revised version appearing as a Penguin paperback under Williams’s editorship in 1968 – reflected a profound disillusionment with the Labour government and aimed to unite a range of influential socialist voices around a coherent programme that would revitalise the Left within the party. The manifesto was ignored (even by the Labour Left’s journal Tribune) and by 1969 Williams had joined Plaid Cymru, the Welsh nationalist party. In the essays collected posthumously as Who Speaks for Wales? (2003), Williams located the language activism of Cymdeithas yr Iaith and the ‘radical minority nationalism’ of Plaid Cymru within the broader coalition of movements – Civil Rights in the USA and Ulster, feminism and the nascent ecology movement – that constituted the New Left. Informed by this new perspective, The Country and the City (1973) is an impassioned critique of dominant, metropolitan, ways of seeing the periphery, and mounts a case for anti-colonial struggle and peasant revolt. Those struggles are, as always for Williams, cultural as much as political or economic, and in this volume the ‘selective tradition’ of the English literary canon is brought up against not only Welsh and Irish texts but also African and Indian sources of inquiry.

Though Williams has been admired for the consistency of his thought, his career can be interpreted as a series of critical self-inventories, for he continued to develop throughout his life. The 1970s saw his greater interest in Welsh intellectual and political debates coinciding with an increasing engagement with European Marxism. These developments were reflected in the essays collected as Problems in Materialism and Culture (1980) (which included ‘The Welsh Industrial Novel’ and ‘Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory’) and Writing in Society (1983) (including ‘Region and Class in the Novel’ and ‘The Crisis in English Studies’). These collections both announced and substantiated what he described as a ‘cultural materialism’ that rejected the close reading traditions of ‘Cambridge English’ and embraced an interdisciplinarity that deliberately sought to undermine the legitimacy of literary study as an isolated discipline. His most theoretical volumes Marxism and Literature (1977) and Culture (1981) belong to this period, as does the remarkable volume of interviews with the editors of New Left Review, Politics and Letters (1979). In that book he combined the divergent trajectories of his thought by describing himself a ‘Welsh European’.

His final substantial volume, Towards 2000 (1983), is an attempt at describing the cultural and political consequences of the rise of the New Right as embodied in the governments led by Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the United States. What Williams described as ‘Plan X’, characterised by the destruction of public common interests in the name of private solutions at home and the expansion of nuclear deterrence to counter an exaggerated external threat abroad, would come to be labelled neoliberalism in later years. The volume also contains Williams’s most extended engagement with national identity, in which he argues that the rejection of the divisive ideologies of race and nation as a ruling-class functionally employs them must not lead to a universalist dismissal of the ‘lived and formed’ cultural identities of diverse, particular, communities.

Raymond Williams’s intellectual career covered a decisive period in the history of the Left: beginning as a key contributor to a New Left seeking a third way beyond Stalinism and social democracy in the 1950s, moving from the anti-war and student movements of the 1960s to Eurocommunism and the new social movements of the 1970s, and ending with the politics of identity and discourse in his final decade. Throughout, Williams responded to the intellectual and political changes around him while remaining committed to a politics of class, an assumption of equality with ordinary people and a resistance to the tendency – manifest in the writings of the Frankfurt School, the New York Intellectuals and of key strains of European Marxism alike – of treating the working class as passive victims, irredeemably corrupted by TV and mass consumption. In an era of dogmatic divisions, Raymond Williams’s instincts were towards conciliation and bridge-building, whether between the humanist and theoretical Left in the 1960s, or the nationalist and socialist strains of Welsh thought in the 1980s. This tendency, which may account for the way he is continually turned to as a resource of hope for the Left (particularly in periods of retreat), can perhaps be traced to his border upbringing in which, as he recalled, ‘we talked about “the English” who were not us, and also “the Welsh” who were not us’. He received honorary degrees from the Open University (1975), the University of Wales (1980) and the University of Kent (1984). His writings have been translated into many languages, including Portuguese and Japanese that reflect the ongoing engagement with his work in Brazil and Japan. He died on 26 January 1988 at his home, 4 Common Hill in Saffron Walden, Essex, and was buried at the Parish Church of St. Clydawg in the Black Mountains of his native border country.