by Dai Smith (Parthian, 2010)

From Rhondda heroes chasing the American dream, to rioters staking a claim in their society, In the Frame is a powerful alternative history of twentieth-century South Wales, offered from the personal viewpoint of cultural historian Dai Smith.

It takes the reader into a territory - a mythical and veritable Dai Country - formed by the influence of writers and painters, boxers and historians, friends and relatives, rioters and correspondents, critics and photographers. As well as the autobiographical overtones of a Tonypandy childhood and distinguished career, In the Frame contains the far wider undertones of a collective biography. It pieces together the consciousness of a society which led its inhabitants in search of fame and fortune as well as the daily struggle for rights and recognition.

Leighton Andrews AM

The speech given by Leighton Andrews AM, Minster for Children,Education and Lifelong Learning, at the book launch of In the Frame.

Dai In the Frame

I might have become a student of Dai Smith’s in the 1970s. I had a place at Cardiff to read English; mucked up my English A level and was offered instead a place at Cardiff to do history; decided I wanted a broader choice and went to Bangor to do both.

Instead, I was to hear the name Dai Smith from historians in Bangor who had met him in Gregynog or other trips. Friends of mine went to study under him. In my case, having left Wales involuntarily as an 11 year-old in 1968, I left voluntarily after the debacle of 1979. I was one of those who was shouting at the television in March 1979 for giving us the wrong result, in the words of one of Dai’s students, Dr Tim Williams, at a History Workshop conference on Patriotism in 1984. So I followed a History Master’s course at Sussex taught by Stephen and Eileen Yeo and based on Raymond Williams’ keywords.

In some ways we have been moving on parallel tracks. I have moved from Barry to Tonypandy. Dai moved from Tonypandy to Barry.

Barry, which Dai calls ‘that unlikely Tonypandy-by-Sea’. The Rhondda writer Gwyn Thomas, who moved to Barry, said the town 'still tingles with the shock of its beginnings'. For a period Gwyn Thomas lived opposite us. Of course, at the age of 6 I didn't know much about him, but I did know he was famous with a capital F and a writer with a capital R.

Dai lives ten minutes walk from my primary school on Barry island; my Rhondda home is ten minutes walk from the Tonypandy street he grew up in, and my constituency office is just down the hill from there. So parallel tracks.

I first read Dai Smith when A people and proletariat came out. Suddenly, I had a proper understanding of where I came from and what it meant to be from South Wales. It was a challenge to the Wales of myths; to the Victorian/Edwardian nationalist liberalism that had ideologically dominated the discourse of Welshness; to the notion that Welsh history depended on some fantasy football team of princes and rebels – who always lost by the way; to the notion that to be really Welsh, you had to speak Welsh; and it reinserted the people back into the place. It paid tribute to the historic particularity of the South Wales experience that gave context to us all as individuals, family members, people in communities – and to a Welsh working class experience that our families shared, even if our parents had made it to the next rung.

It was explosive, and it was part of a movement. Dai then and now was asserting what he calls ‘the case for the exceptional nature of that world….across the broader British spectrum’, as he says on page 351, just to prove how much of the book I’ve read!

Dai speaks of psychobiography and its importance - uniting the history of family, community and class. ‘My true subject’, says Dai, ‘is consciousness….and the actions which consciousness caused the people of this Welsh world to take.’ It is the consciousness that a member of the Rhondda Labour Women’s Forum described to me on Sunday, when she spoke of the coach trips from the Rhondda in the 1960s and 1970s to trade union and political conferences in Llandudno, pausing only to hiss at the statue of Rhondda coal-owner David Davies as the bus passed through Llandinam.

It is the story of us all – the contours of our family histories shaped by the fast moving torrent of emerging industrial capitalism in South Wales – in my grandmother’s case the move to Barry from rural sea-faring West Wales after the docks were built, my great grandfather’s move to the Rhondda from the Forest of Dean in the early 1900s, then the move out of the Rhondda after WW1.

This relationship of the personal and the social, of course, is what Dai Smith has recognised, in his magisterial account of the first 40 years of Raymond Williams’ life, talking of Williams’ own parents:

‘The young man and his wife had already seen how the rhythm of their private intimate lives moved to the beat of circumstances and forces that paid little notice to their individual wills. They had understood what connected them to others like them without ever wishing that their own particularity be submerged.’

It is what Raymond Williams saw in Dai Smith, writing in Arcade magazine 30 years ago, when he said:

‘Every reader of this new history will find, at some point, a moment when his own memory stirs and becomes that new thing, an historical memory, a new sense of identity and relationships…The personal memory, local and specific, is then suddenly connected with the history of thousands of people, through several generations. As the particular and the general, the personal and the social, are at last brought together, each kind of memory and sense of identity is clarified and strengthened. The relations between people and ‘a people’ start to move in the mind.’

Now briefly to Dai the writer.

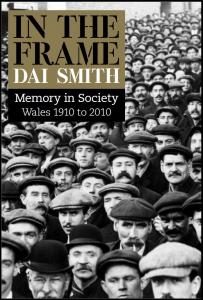

He is a poet manqué. He calls the Rhondda South Wales ‘throbbing central vein’. He is a novelist manqué. If you have doubts, read Dai’s 3 page interpretation of Levi Ladd’s photograph of the Tonypandy rioters. This is a novelist’s creative rendering, or at least a literary critic’s. We all know of Dai’s love of exuberant language. It is no surprise that he writes in Aneurin Bevan and the world of south Wales of both Raymond Chandler and Gwyn Thomas. Sometimes the exuberance ‘is as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel cake’ as Raymond Chandler put it. This is the language of American Wales – the language of the Rhondda, those parts of America that never made it to the boat, as Gwyn Thomas had it.

Sentences that kick you in the solar plexus while simultaneously picking your pocket.

Dai has always been a very good model of the public intellectual. He has always been a cultural activist. He recalls on page 161 of his book constructing courses in Welsh writing through the medium of English ‘within a History Department because nothing so vulgar then sullied any major university English department’. Later, following our work in the Assembly culture committee in 2003 and 2004, he would become the Editor of the Library of Wales.

I first met him when I was at the BBC in London and he was at BBC Wales. I remember he came to Brussels for a week of BBC events and fulminated at how the diplomatic class had adopted the phrase ‘Brits’ – an anti-colonial insult – as an ironic shorthand for themselves and other ex-pats. I remember being with him at a BBC Senior Management Conference in London in the summer of 1996. Tony Blair had just announced there would be no devolution in Wales without a referendum. Some were concerned about this. Dai and I were both convinced of the necessity for a vote to reverse 1979 if the new institution was to have legitimacy. The Assembly had to be a popular institution, endorsed by the people of Wales, not a hand-me-down from the crachach.

You will I am sure recall the words of Raymond Williams in Culture and Society when he says:

‘The working class, because of its position, has not, since the Industrial Revolution, produced a culture in the narrower sense. The culture which it has produced, and which it is important to recognize, is the collective democratic institutions, whether in the trades unions, the co-operative movement, or a political party.’

In the Welsh context, we can now add the National Assembly for Wales to that list of consciously created cultural institutions.

At the Arts Council, Dai remains a cultural activist and a public intellectual. Next week Spectacle Theatre, supported by the Arts Council, is producing its community play on the Tonypandy Riots, Tales from the Horse’s Mouth. I doubt whether Arts Council support would have happened without Dai’s leadership.

So I am delighted to be here today to launch Dai’s book. Dai spoke ten days ago in Llwynypia about the Tonypandy Rioters ‘breaking the rules’. I like to think that part of the point of having a National Assembly is to allow us all now and again to break the rules. And nobody breaks them better than Dai.